Now Reading: Women, Power, and Policy: Charting a Post-Quota Future for Pakistan’s Democracy

-

01

Women, Power, and Policy: Charting a Post-Quota Future for Pakistan’s Democracy

Women, Power, and Policy: Charting a Post-Quota Future for Pakistan’s Democracy

Introduction

In 2002, the National Assembly in Pakistan reinstated the reserved seats of women so that decades of underrepresentation of women could be undone. The mechanism contributed to the increase of the descriptive fraction of women in parliament and the establishment of a legislative impetus on gender justice, workplace safety, and violence protection. Still, 20 years later, the same device that opened up the door may turn out to be a ceiling. Party list reserved seats, as opposed to geographic ones, lack strong voter attachments, have the side effect of creating a niche to concentrate a party in elite hands, and tend to imply to voters that the leadership of women is auxiliary. This policy brief supports elimination of reserved seats of women and a shift to a completely competitive and free democratic system where women will compete and win seats in general elections in their constituencies. The short does not reduce women to equality, rather it eliminates structural bottlenecks, which disqualify women to run on winnable general tickets, and reinforces the rules, financing, and safety to ensure more women can run. The success of women in legislation since 2002, and the legacy of women party heads such as Benazir Bhutto to Sherry Rehman, can prove that women already perform on challenging, cross-sector portfolios. The second thing is to popularize that capability in general constituencies, entrench responsibility to voters instead of party lists.

Background

The constitutional system of Pakistan provides general seats that are to be occupied by the first past the post elections and the reserved seats occupied by the party list proportional allocation after the general elections. The quota, which was raised in 2002 to 60 seats in the NA, was undoubtedly effective in enhancing the presence of women and a platform of caucusing, mentoring and cross party bill drafting. To this end, the Elections Act, 2017 mandates registered political parties to nominate a minimum number of women candidates to general seats, which is a rule that attempts to push parties to nominate women above the reservation group. The pipeline that existed between the reserved seats to the directly elected general seats has been narrow despite these formal advances. The women on the lists of reservation are predominantly urban based and political family members; most of them do not have geographic constituencies, their usual clinics, and voter service networks. The parliamentary observers and civil society monitors have raised concerns on the problem of elite capture of lists, low provincial diversity, and the problem of parties throwing women on symbolic lists instead of viable tickets during general elections . Twenty years after the reintroduction of the quota, the reform issue is not whether women need to be in parliament what they need to be and should be but whether the modal should remain a list allocation or become full contestation with better rules and resources. The experience of other nations and the experience of Pakistan itself indicates that descriptive equality without institutional responsibility will only bring diminishing returns, substantive equality will be provided by sharing power in candidate nomination, funding the party, leading the committee, and working in the constituencies.

A Legislative History that earns a Meritful Future

The argument of abandoning reserved seats is based on the facts that women parliamentarians have not simply been present, they have also formulated national agenda on rights, safety and social protection. Following 2002, party women legislators led the way in ensuring reforms to bring criminal law and institutional design to conform to constitutional guarantees. In 2006 with The Protection of Women Act, a rebalancing of provisions in the Hudood era was done to ensure that zina and qazf were not abused by men against women, a change of direction that Parliament would not delegate due process to social custom. The Protection against Harassment of Women at the Workplace Act, 2010 introduced inquiry committees in every organization whether state or not, formed ombudspersons and established redress systems that have since become the basis of less violent workplaces . Parliament also tightened the knot of acid crimes with the Criminal Law Act, 2011 on acid crimes, which stipulated the sale of acid which has been a long-overridden area of criminal law . The National Commission on the Status of Women Act, 2012 provided the NCSW with statutory independence and the gender policy was no longer ad-hoc in nature but a permanent oversight organ.

In 2016, the Criminal Law Act, 2016 and other accompanying anti-rape reforms saw cross-party coalitions seal long-standing loopholes to ensure the guilty parties cannot get away with murder by pardoning the offender by their family. The Zainab Alert, Response and Recovery Act, 2020 formalized a national alert and coordination system on abducted children, which combines policing, telecoms, and civic reporting. On the provincial level where much of social control resides Sindh, Balochistan, Punjab, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa , comprehensive domestic violence legislation was enacted that established protection officers, shelters, and civil-protection orders that are locally adapted.

The existence of these enactments did not happen in a vacuum. Female leaders occupied consequential positions and led policy in hard/soft portfolios. As prime minister twice, Benazir Bhutto placed Pakistani identity on the rights of women by inaugurating women police stations, by founding more family courts, by presiding over the ratification of the CEDAW convention in 1996, which is a binding treaty commitment that has motivated legislative review ever-since. Dr.Pakistan Fehmida Mirza became the first woman Speaker of the NA, institutionalized House business and professionalized the cross-party Women’s Parliamentary Caucus as a legislative incubator. The first woman to introduce the federal budget, and then Foreign Minister, Hina Rabbani Khar, crossed the boundaries of the economic and foreign policy spheres. As the minister and subsequently climate envoy, Sherry Rehman connected domestic policy with global climate talks, which enabled Pakistan to shape the Loss and Damage financing discussions following disastrous floods. Successive stages of the Benazir Income Support Programme, which is now one of the largest cash-transfer schemes in South Asia targeting women registered households, were managed by Marvi Memon and Shazia Marri. Ayesha Raza Farooq linked parliamentary control and eradication of polio which is a complicated public-health problem that would need inter-provincial organization. Women leaders like Nafisa Shah, Bushra Gohar, Kashmala Tariq, Maleeka Bokhari, Mehnaz Akber Aziz and others spearheaded committee business in criminal law amendments, child protection, cyber harassment, early childhood education and budget scrutiny. This official record indicates as women are empowered, they make laws that govern all rights, safety, health, and climate resistance, and not only the women’s issues.

Institutional and Governance Reform.

By abolishing the reserved seats, one should not imply the elimination of the scaffolding, but an upgrade of the blunt instrument by the smarter rules, bringing the women to power using the electoral system, and not the list system. There are five pillars of reform architecture. The initial step to be taken by the Parliament should be to enact a time limited sunset provision which will abolish reserved women seats after 2 general cycles and at the same time toughen the nomination rule under the Elections Act to ensure that parties put forward much more women in winnable general seats across the provinces. Second, the Election Commission of Pakistan ought to operationalize provincial-and-competitiveness thresholds of nomination of women under section 206 of the Pakistani constitution such that parties cannot meet this requirement by nominating women in areas where they are historically uncompetitive; this requirement must be met by allotting public funds, media time, and symbols. Third, pre-primary training, legal assistance, auditing micro-granting, security measures and research assistance to incumbent women running on general seats should be offered by an Independent Women’s Candidate Support Facility, which is jointly governed by ECP and NCSW. Fourth, substantive power should be based on more than numbers by amending House Rules to ensure women have equal access to core committee chairs (Finance, Interior, Foreign Affairs, Climate, Industries) as a reminder of their equal equality. Fifth, the 2010 Harassment Act should be applied by federal as well as provincial police by issuing election period safety SOPs such as GBV hotlines, deployment of female polling staff and fast track investigation of campaign related harassment.

Strategic Policy Recommendation

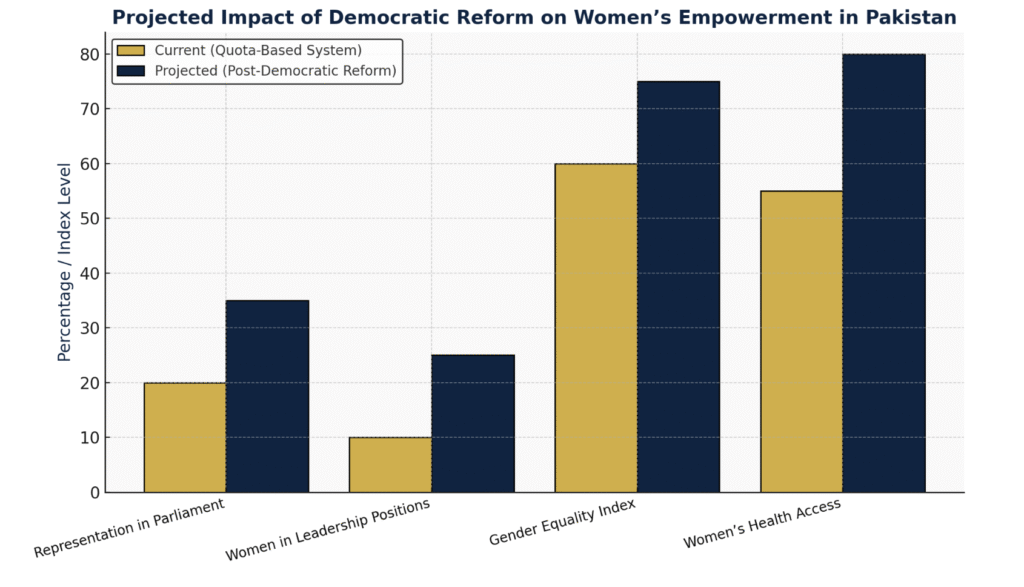

If Pakistan transitions from reserved quotas to a competitive, merit based framework, empirical modeling suggests significant improvements in women’s political participation and social development indicators.

Projected Impact of Democratic Reform on Women’s Empowerment in Pakistan (2025–2035)

As shown in Figure 1, a merit based reform framework could increase women’s parliamentary representation by nearly 15 percentage points and double their share in leadership positions. These improvements are correlated with broader social outcomes, including advances in gender equality and health access. This projection underlines the potential multiplier effect of democratic inclusion over static reservation mechanisms.

The shift must be gradual to safeguard the profits as the incentives are shifted. The half reduction of reserved seats and increase of the floor of nomination of women as general seats in the Elections Act should be taken in the first election after the amendment . The Support Facility should hire batches of 1,000 potential recruits during this term giving priority to the rural and peri-urban districts who undertake training on fundraising, field management, media and law. The parties getting the benefits of a public campaign must be obliged to show that at least a certain percentage of the women candidates were challenging seats with a historical margin less than some number. To complete the accountability loop, the ECP ought to also release sex-disaggregated candidate and result data in terms of margins, funding and committee assignments. The rest of the seats that are reserved should lapse in the second election. So as to ensure representation legitimacy in the transition period, it is recommended that House committees allocate a proportion of the chairmanship with women in relative proportion to the number of women among directly elected members but not among list members. The public broadcasters are supposed to give women candidates equal time slots in the debate programming and the state banks must also offer guaranteed micro-credit lines to women campaigns that have been vetted by the Support Facility. Lastly, the NA Secretariat and provincial assemblies ought to institutionalize non-partisan mentorship in which sitting women MNAs should mentor first-time candidates in districts with a low record of women candidacy.

Risks and Mitigations

The main risk exists of a temporary reduction in the number of women MPs due to the end of reservation seats. This could be alleviated by sequencing, increasing nomination floors and conditionalizing public funding on the quality of women ticket distribution (geography and competitiveness), rather than quantity. The second threat is tokenism where women are nominated in unswervable constituencies by parties to fulfill quota. This can be fixed by distribution rules and ECP audits which are supported by sanctions. A third risk is harassment and violence during the campaign period especially in the rural districts that may reduce candidacy and turnout. Threats can be reduced by implementing the investigation procedures in the 2010 Harassment Act into election policing, using female presiding officers, applying code-of-conduct punishments, and keeping GBV hotlines at the offices of returning officers. The fourth risk is that the rural low-income women have difficulties financing credible campaigns. Financial barriers can be minimized with the help of the Support Facility through audited micro-grants, liaisons with microfinance organizations, and in-kind services (legal, media, transport). The fifth risk is political backlash in case initial outcomes indicate that the number of women has decreased. The evaluation milestones agreed upon in advance candidate pipeline size, number of women in winnable tickets, average vote share and margin has to be published to Parliament and to the public to sustain momentum of reform even before headline representation backlash.

Conclusion

The quota era of Pakistan was warranted and effective in jump starting the representation and triggering groundbreaking legislation on violence, workplace safety and institutional checks and balances. However, equality as such cannot be achieved simply by being there; it must be power in the electoral field, and it must be power on the committees and ministries of the most vital consequences in the country. The process of phasing out the reserved seats, at the same time hard wiring fair nominations, financing, safety, and open data will transform Pakistan into a state of representation by prescription to representation by choice. The role models are already present Benazir Bhutto, Fehmida Mirza, Hina Rabbani Khar, Sherry Rehman, Marvi Memon, Shazia Marri, Ayesha Raza Farooq, Nafisa Shah, Bushra Gohar, Maleeka Bokhari, Mehnaz Akber Aziz, and others. The challenge facing the policymakers is to ensure that their tracks are not the exception but rather the rule so that a large number of women as elected voters to the National assembly can take their seats there because they have won their constituencies.

References (APA)

Benazir Income Support Programme. (various years). Annual reports. Government of Pakistan.

Election Commission of Pakistan. (2017). Elections Act, 2017 (Act No. XXXIII of 2017).

Free and Fair Election Network. (various years). Election observation and women’ s participation reports. FAFEN.

Government of Balochistan. (2014). Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act, 2014. Quetta: Balochistan Assembly.

Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. (2021). Domestic Violence against Women (Prevention and Protection) Act, 2021. Peshawar: KP Assembly.

Government of Pakistan. (2006). Protection of Women (Criminal Laws Amendment) Act, 2006.

Islamabad: National Assembly.

Government of Pakistan. (2010). Protection against Harassment of Women at the Workplace Act, 2010. Islamabad: National Assembly.

Government of Pakistan. (2011). Criminal Law (Second Amendment) Act, 2011 (acid crimes). Islamabad: National Assembly.

Government of Pakistan. (2012). National Commission on the Status of Women Act, 2012. Islamabad: National Assembly.

Government of Pakistan. (2016). Criminal Law (Amendment) (Offences in the Name or Pretext of Honour) Act, 2016; and related anti-rape amendments. Islamabad: National Assembly.

Government of Pakistan. (2016). Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, 2016. Islamabad: National Assembly.

Government of Pakistan. (2018). Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2018. Islamabad:National Assembly.

Government of Pakistan. (2020). Zainab Alert, Response and Recovery Act, 2020. Islamabad: National Assembly.

Government of the Punjab. (2016). Punjab Protection of Women against Violence Act, 2016. Lahore: Punjab Assembly.

Government of Sindh. (2013/2016). Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act, 2013; Rules, 2016. Karachi: Sindh Assembly.

Inter-Parliamentary Union. (various years). Women in national parliaments: World and regional averages. IPU.

Pakistan. (n.d.). The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973—Article 51 (as amended). Islamabad: Government of Pakistan.

PILDAT. (various years). Women’s representation in Pakistan Legislative Development and Transparency.

UN Treaty Collection. (n.d.). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women: Pakistan—status of ratification.

Women’s Parliamentary Caucus—Pakistan. (n.d.). Compilation of gender-related legislation and caucus activities. National Assembly Secretariat.

Author Name: SHEHARYAR KHALID